Dani’s Blog

Thank you, Yuyo. Safe travels in the au-delà

As with all passings, I have many emotions swirling. I have deep sadness, because he was such a generous artist and human, sharing so much of his time, vision and creativity. I had the great fortune to be able to photograph his process when he created his monumental work for the Venice Biennale in 2009.

Version français ci-dessous

I learned this week that Yuyo Noé has left his body. As with all passings, there are many emotions swirling. I have deep sadness, because he was such a generous artist and human, sharing so much of his time, vision and creativity. I had the great fortune to be able to photograph his process when he created his monumental work for the Venice Biennale in 2009.

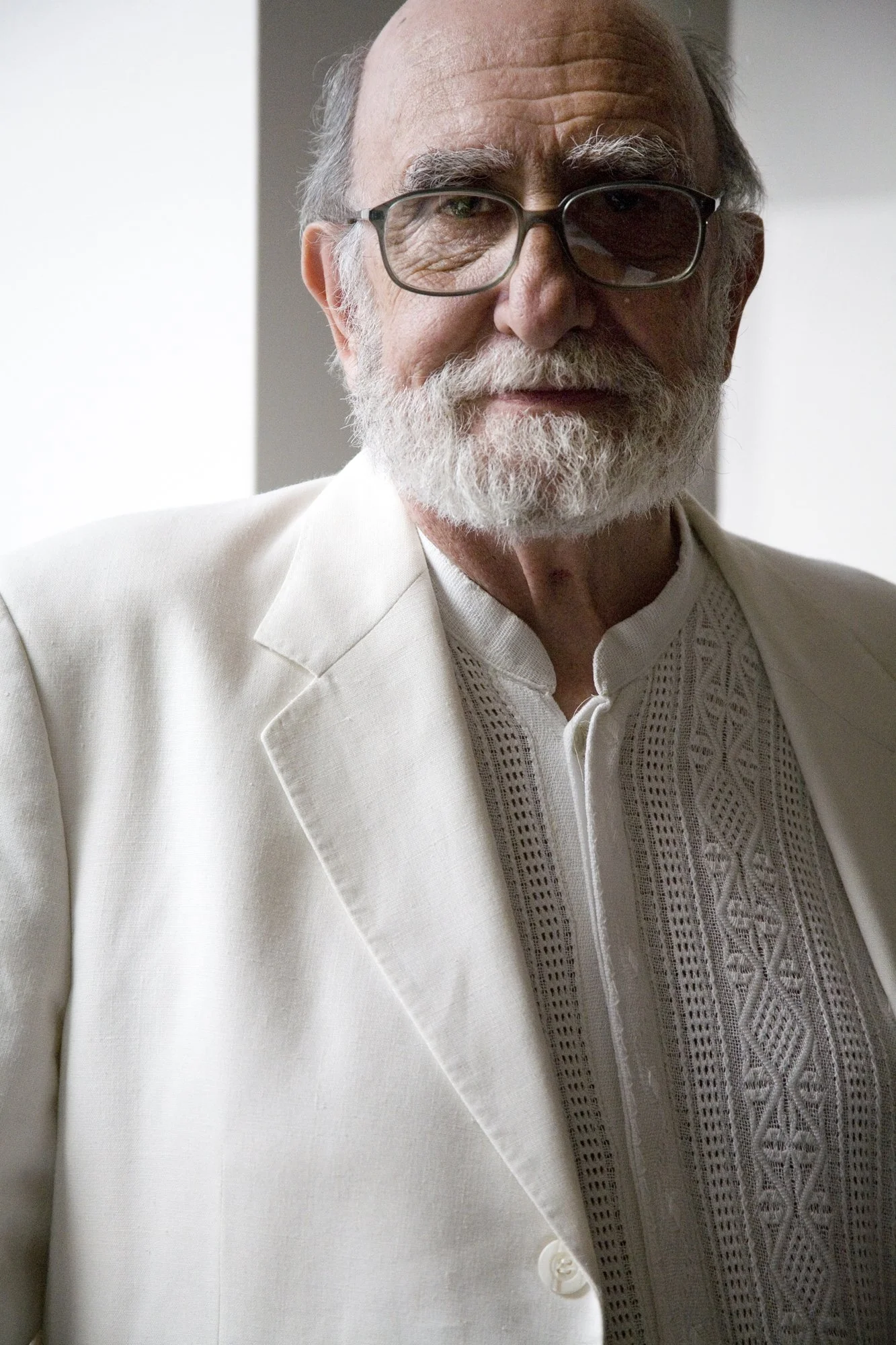

Yuyo Noe at the Central Park studio in Barracas, Buenos Aires, working on Red/Net for the Venice Biennale.

He was 75 at the time, and worked late into the night, listening to Bach and drinking a gin & tonic. I could’ve watched him paint for hours, but at some point I’d go home, and when I came to the studio the next morning, I’d always be amazed by how much more he’d created after I left.

From those days in Argentina, spent with Yuyo and many other talented artists, I understood that when you spend your time making art, or anything that lights you up, on a daily basis, working from your heart and soul, it keeps you “young,” or rather feeling alive and purposeful. We talk about that a lot now, but easily forget. My time with these artists helped me see it, feel it, understand it. And in the years since that biennale, I saw Yuyo in Paris several times, and always felt like his creativity was a strong motor.

Yuyo painting late at night at his home on Tacuari, Buenos Aires.

Witnessing his work ethic was inspiring, and an example of dedication. Being in this kind of creative soup helped me give myself permission. His family was so different than my own. His daughter is an artist as well, and I’ve always felt like her art-making is a strong spark of life-force, something timeless in her. Whereas her family would consider her “day job” as a waste of time, and her art-making to be the real work, for my Midwestern American family it’s the opposite. The trick, I gather, is finding your own balance on your journey forward.

A moment in Yuyo’s process.

Watching Yuyo’s creative process opened up many doors to freedom in my mind. As he ripped off pieces of what he’d painted the night before, integrating it onto the large canvas, I almost held my breath. Observing him, I felt a childlike, “let’s try it! it’s fun!” but also saw a clear mastery and vision behind the act.

As luck would have it, I showed up on the first day they began working at the re-converted match stick factory named Central Park, in Barracas, Buenos Aires. It was the day they draped the canvas onto its huge frame. My Spanish wasn’t so great, so throughout those three months, I made prints and distributed them to his team, to show what I was doing. This was before instagram and smart phones.

Yuyo in action one night, on a fresh roll of paper.

Some of Yuyo’s brushes.

It’s hard to select photos to share from my time documenting his work and process. There are so many.

In remembering Yuyo and his work, the warm family of friends that surrounded him and welcomed me, I have deep gratitude. It brought vibrant colors to my dreams and opened up doors of perception.

In my work, I put everything into a frame, with a certain obsession for geometry, which Cartier-Bresson said was necessary for a photographer. Being with Yuyo’s paintings, observing him creating, loosened my tight fist on geometry and relaxed my thirst for a certain order, learning to appreciate a different kind of order in chaos.

Yuyo adding details with a white pen.

Yuyo, wherever you are now, I wish you peace and joy, seeing how your work and care and vision expands through each person that you touched during your time here. Give a hug to your dear Nora. Thank you for opening your home, your studio, and your heart. I’ll pay it forward in your honour.

Merci, Yuyo. Bon voyage dans l’au-delà.

J’ai appris cette semaine que Yuyo Noé a quitté son corps. Comme pour chaque départ, un tourbillon d’émotions s’est levé. J’éprouve une grande tristesse, car c’était un artiste et un être humain d’une générosité rare, partageant tant de son temps, de sa vision et de sa créativité.

J’ai eu la grande chance de pouvoir photographier son processus lorsqu’il a créé son œuvre monumentale pour la Biennale de Venise en 2009.

Il avait alors 75 ans, et travaillait tard dans la nuit, écoutant Bach, un gin tonic à côté. J’aurais pu le regarder peindre pendant des heures, mais à un moment donné je rentrais chez moi, et le lendemain matin en revenant à l’atelier, j’étais toujours émerveillée par tout ce qu’il avait encore créé après mon départ.

Pendant ces journées passées en Argentine, avec Yuyo et de nombreux autres artistes talentueux, j’ai compris qu’en consacrant son quotidien à créer — à faire ce qui vous anime — avec le cœur et l’âme, on reste “jeune”, ou plutôt vivant et habité d’un sens profond. On en parle beaucoup aujourd’hui, mais on oublie vite. Le temps passé auprès de ces artistes m’a permis de le voir, le sentir, l’intégrer.

Et dans les années qui ont suivi cette biennale, j’ai revu Yuyo plusieurs fois à Paris, et j’ai toujours senti que sa créativité était un moteur puissant.

Être témoin de son éthique de travail était inspirant — un exemple de dévouement. Être plongée dans cette “soupe” créative m’a permis de m’autoriser à faire pareil. Sa famille était si différente de la mienne. Sa fille est aussi artiste, et j’ai toujours perçu dans sa pratique une étincelle vitale, une force intemporelle. Là où sa famille considérait son “job alimentaire” comme une perte de temps et sa pratique artistique comme le vrai travail, dans ma famille américaine du Midwest, c’était exactement l’inverse. Le défi, je crois, est de trouver son propre équilibre sur le chemin.

Observer le processus créatif de Yuyo a ouvert de nombreuses portes dans mon esprit. Lorsqu’il déchirait des morceaux de peinture de la veille pour les intégrer à la grande toile, je retenais presque mon souffle. En le regardant faire, je ressentais une joie enfantine — “allez, on essaie ! c’est marrant !” — mais je voyais aussi une maîtrise et une vision très claires derrière l’acte.

Le hasard a bien fait les choses : je suis arrivée le tout premier jour du travail à la fabrique d’allumettes reconvertie, appelée Central Park, à Barracas (Buenos Aires). C’était le jour où ils ont tendu la toile sur son énorme châssis. Mon espagnol n’était pas terrible à l’époque, alors pendant ces trois mois, j’ai tiré des épreuves que je distribuais à son équipe, pour montrer ce que je faisais. C’était avant Instagram et les smartphones…

C’est difficile de choisir quelles photos partager de ce moment passé à documenter son œuvre et son processus. Il y en a tant.

En me souvenant de Yuyo, de son travail, et de la chaleureuse famille d’amis qui l’entourait et m’a accueillie, je ressens une profonde gratitude. Cette période a mis des couleurs vives dans mes rêves et ouvert de nouvelles portes de perception.

Dans mon travail, j’ai toujours tout cadré avec une certaine obsession pour la géométrie — obsession que Cartier-Bresson disait nécessaire pour un·e photographe. Être auprès des toiles de Yuyo, le voir créer, a relâché cette crispation, détendu mon besoin de rigueur, et m’a appris à reconnaître un autre type d’ordre dans le chaos.

Yuyo, où que tu sois maintenant, je te souhaite la paix et la joie, en voyant combien ton œuvre, ta bienveillance et ta vision continuent à se diffuser à travers chaque personne que tu as touchée durant ton passage ici. Embrasse ta chère Nora. Merci d’avoir ouvert ta maison, ton atelier et ton cœur. Je continuerai à transmettre, en ton honneur.